Workplace Law Reform Resources

The Secure Jobs, Better Pay Act: Overview

The most substantial reforms to workplace legislation in over a decade, with 249 pages of legislative amendments to the Fair Work Act 2009 (Cth) (FW Act), and associated legislation, in over 27 categories.

There has been substantial reregulation of workplace relations with increased discretionary powers for the Fair Work Commission (FWC) and new and expanded areas of liability for employers.

The changes can be divided into four major areas.

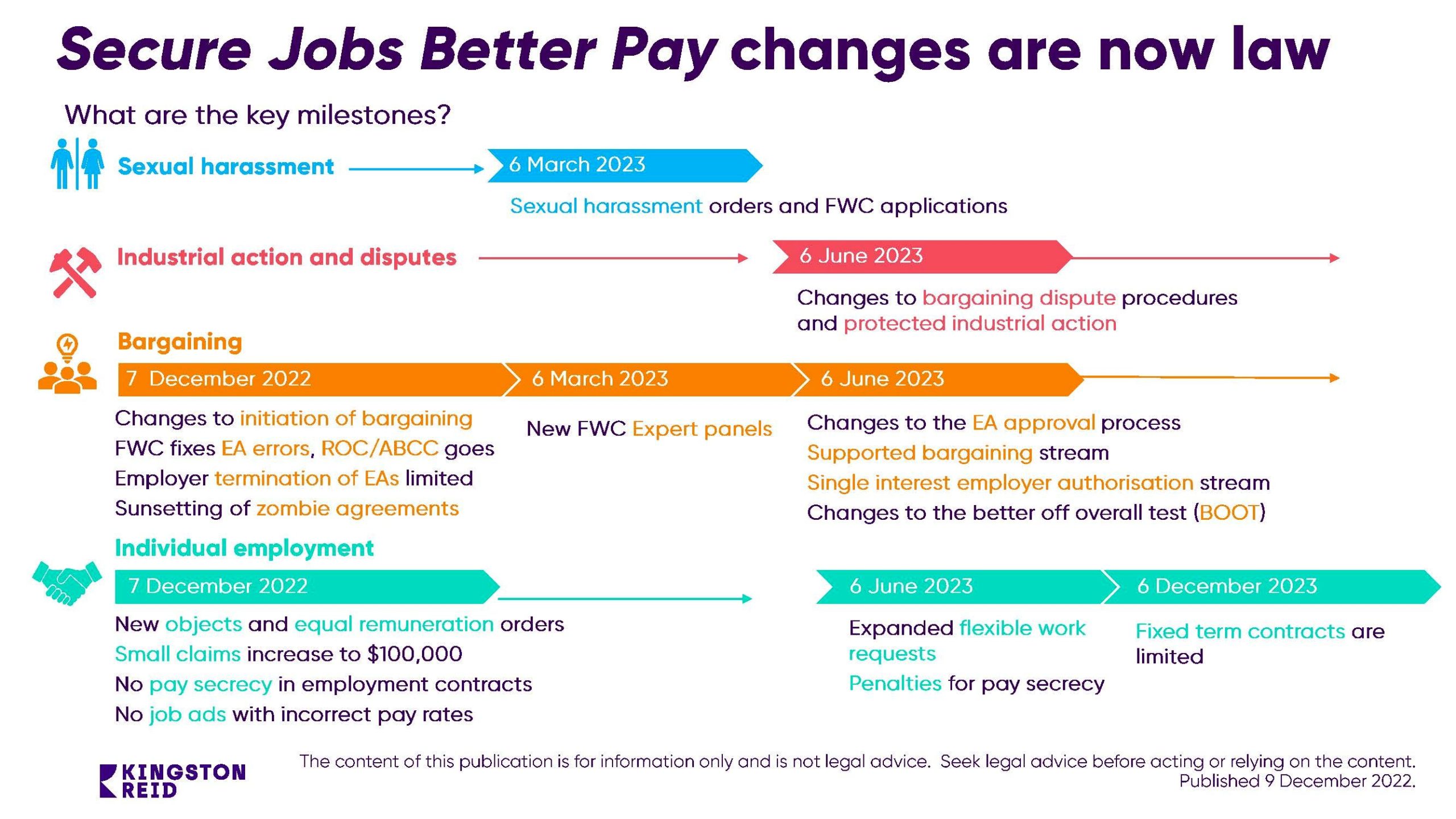

The Secure Jobs, Better Pay Act (Act) was passed on 2 December 2022 and received royal assent on 6 December 2022. The changes will take effect according to the following timetable.

Changes to enterprise bargaining

Some of the most significant changes to the FW Act are in enterprise bargaining. Enterprise bargaining is where the terms and conditions of employment are set at an individual enterprise level. Prior to the legislative reform, unions were critical of employers who decided to abandon bargaining and set terms and conditions contractually. Employers were often of the view that the pre-approval requirements meant that enterprise bargaining was no longer viable. The key changes to the current enterprise bargaining system will:

- make it easier for employees and unions to initiate bargaining where an employer may not be willing to

- open new avenues for employee and union initiated multi-employer bargaining; and

- simplify the process for agreement making and approval.

At the same time, it will be much harder for employers to terminate enterprise agreements that no longer meet the needs of the business or to make use of selective enterprise bargaining which is not representative of the workforce the proposed agreement will cover.

This new environment will be very challenging for employers, however strategic opportunities will arise from the changes which can be beneficial for business.

Enterprise bargaining generally

Initiating Bargaining

Employee organisations (unions) can now more easily start the process of enterprise bargaining with an employer without the employer’s consent in certain circumstances, including where:

- the proposed single-employer agreement will replace an earlier single-employer agreement

- it is less than five years since the earlier agreement’s nominal expiry date; and

- the proposed agreement will cover the same, or substantially the same, employees that were covered by the earlier agreement.

These changes operate with the provisions relating to bargaining orders and allow unions to apply to the FWC for bargaining orders where they have made a written request to an employer to bargain for an agreement.

Genuine agreement test

The process for the FWC to approve enterprise agreements from June 2023 is being simplified to move away from the current prescriptive steps that must be met by employers. The FWC will need to undertake a singular broad analysis of whether the agreement has been genuinely agreed by the employees it will cover. The FWC’s analysis of whether there is genuine agreement will be guided by a Statement of Principles that will be published by the FWC and deal with:

- informing employees about bargaining and their right to be represented by a bargaining representative

- providing employees with a reasonable opportunity to consider a proposed agreement and become informed about it prior to a vote

- explaining the proposed agreement terms and their effects

- providing employees with a reasonable opportunity to vote on an agreement; and

- any other matters the FWC considers relevant.

While the goal is to simplify the process, the increased discretion given to the FWC will make it very important for employers to be aware of the Statement of Principles and monitor how it is applied in decisions of the FWC.

Coverage requirements and bargaining in good faith

There will also be a new barrier to the approval of enterprise agreements where they have not been made as a result of collective bargaining in good faith. This includes where there is a low voter cohort and a selection of employees who are not representative of the broader workforce. This may mean that the coverage requirements are not met where:

- no genuine collective bargaining in good faith occurred during the agreement-making process

- an agreement is proposed to cover employees across a wide range of industries, occupations or classifications, but the voting cohort included only employees engaged in a single industry, occupation or classification; and

- a small cohort of employees has voted on an agreement proposed to cover a wider workforce.

Changes to the Better Off Overall Test

From June 2023, the Better Off Overall Test (BOOT) will be simplified with the intention of removing the unnecessary complexity that is caused by the FWC currently conducting a line-by-line assessment of a proposed enterprise agreement against the terms of the underlying Modern Award.

The new provisions will require the BOOT to be applied as a global assessment, with the FWC having regard only to patterns or kinds of work, or types of employment, that are reasonably foreseeable at the time of the BOOT.

Where an agreement does not satisfy the BOOT, the FWC will be empowered to amend or remove that term to allow the agreement to pass the BOOT. It is the FWC and not the employers, employees or unions, that decides on amendments – although the FWC must consider their views.

Employers, employees and unions will have the ability to re-apply to the FWC for a reconsideration of whether an enterprise agreement passes the BOOT in circumstances where the work or types of employment covered by the agreement have changed since the FWC initially considered the application for approval of the enterprise agreement. If the FWC is concerned that the enterprise agreement no longer passes the BOOT, the FWC could either accept an undertaking or amend the agreement.

Fixing errors

The FWC can now vary an enterprise agreement to correct or amend an obvious error, defect or irregularity, such as a typo or obvious omission, on its own initiative or on an application by any party to an enterprise agreement.

If the FWC has approved the wrong version of an agreement, such as where an earlier draft of an agreement was submitted by mistake, the FWC can confirm its approval decision as if the correct version of the agreement had been submitted for FWC approval. This can occur on the FWC’s own initiative or on application.

Termination after nominal expiry date

The FWC now must consider the interests of employees covered, before making a decision to terminate an enterprise agreement. This completely changes the current public interest test for termination applications and will have major ramifications for the termination of an enterprise agreement.

Termination of enterprise agreements will only be permitted where one of the three requirements are satisfied:

- continuation would be unfair to employees

- it does not and is unlikely to cover any employees; or

- continuation would threaten the business’ viability, termination would reduce risk of redundancy, insolvency or bankruptcy and the employer has guaranteed employee termination entitlements.

If employees are given a guarantee in relation to their termination entitlements, it will remain in effect for four years, unless otherwise approved by the FWC. Breaching the guarantee will give rise to civil remedy claims.

There are new provisions to bring zombie agreements to an end.

Multi-employer bargaining

The current multi-employer bargaining system from June 2023 will be replaced by three distinct streams bargaining for single-interest agreements, supported bargaining agreements and co-operative workplace agreements. Each stream will require representation by an employee organisation. However, the FWC can also make orders excluding persons, such as unions, from participating in bargaining if they have a history of non-compliance with the FW Act, specifically if they have contravened a civil penalty provision or committed an offence against the FW Act in the last 18 months.

Single-interest agreements

From June 2023 the changes extend to who can apply to the FWC for a single-interest employer authorisation, which compels more than one employer to engage in bargaining for a common enterprise agreement. This has been referred to as multi-employer bargaining. In particular, employee bargaining representatives (including unions) can do so where the application is supported by the majority of the relevant employees.

Once a multi-employer enterprise agreement is in place, unions can apply to the FWC for the agreement to be varied to include additional employers and their employees.

Supported bargaining agreements

Supported bargaining will replace the existing low-paid bargaining stream for employers with identifiable common interests in sectors or industries that have prevailing low pay and conditions, such as aged care, disability care and early childhood education and care. Importantly, the legislative changes grant the Minister power to declare an industry, occupation or sector eligible for the supported bargaining stream, meaning there is a possibility that this won’t be restricted to low paid sectors.

An employer covered by a supported bargaining authorisation will be unable to make any other kind of enterprise agreement with its employees and any existing single-enterprise agreements applying to the employees covered by the authorisation will cease to apply. Once a supported bargaining agreement is in place, unions can apply to the FWC for an order varying the agreement to cover additional employers and their employees, which the FWC must make if it is satisfied that a majority of the employees want to be covered by the agreement.

Employers who have an existing in-term single-enterprise agreement in place will not be covered by a supported bargaining authorisation unless the FWC considers the existing agreement was made primarily for the purpose of avoiding a supported bargaining authorisation.

Cooperative workplace agreements

Cooperative workplace agreements replace the existing multi-employer bargaining stream. Cooperative agreements remain voluntary for employers to participate in where they are not subject to a supported bargaining authorisation immediately before making the agreement.

Industrial action can not be taken in respect of bargaining for a cooperative workplace agreement and FWC intervention, including conciliation and arbitration, is available to the parties by consent.

Industrial action (strikes, lock outs and bargaining disputes)

The changes to the industrial action provisions in the FW Act change the current balance of power where bargaining leads to employees organising to take strike action and employers responding with lock outs. The changes make it easier for unions to satisfy the preliminary steps for taking industrial action. However, they also introduce two new practical hurdles which require forced mediation and allow the potential for the FWC to intervene and impose an enterprise agreement outcome on the parties before industrial action can be taken. These changes will disrupt the current approach that has dominated union and employer strategies where agreement cannot be reached.

Bargaining disputes

Intractable bargaining declarations will replace serious breach declarations and determinations.

Any bargaining representative can apply for an intractable bargaining declaration.

The FWC will make the declaration where:

- the FWC dealt with a bargaining dispute

- the applicant participated in the dispute

- there is no reasonable prospect of agreement; and

- it is reasonable in all the circumstances to do so.

The FWC can then order a post-declaration negotiation period for a specified time.

The Full Bench of the FWC may make an intractable bargaining workplace determination if there are still outstanding disputes after the declarations. The FWC will determine the outstanding issues in dispute, with the FWC determination becoming part of the agreement and binding on the employer and employees. This effectively expands the FWC’s powers and allows it to impose agreement terms (including in relation to pay and conditions) on the bargaining parties. The FWC can make an intractable bargaining workplace determination that becomes a binding part of the agreement.

This means that unions and employers have an alternative source of leverage to protected industrial action and bargaining strategies will need to change.

Industrial action

If the FWC makes a Protected Action Ballot Order (PABO), it must also make an order that directs all bargaining representatives to attend a mandatory conciliation conference before the ballot closes. If any bargaining representative fails to attend, any subsequent action they take will not be protected industrial action.

Mandatory conciliation to take place on or before the ballot closes, non-attendance invalidates industrial action.

Employees still have 30 days from PABO results to commence industrial action and must provide either three days’ notice (for single enterprise agreements) or 120 hours’ notice (for multi enterprise agreements) or up to seven days’ notice (if ordered by the FWC).

Where employee claim action relates to a single-interest employer agreement or a supported bargaining agreement, employees must provide at least 120 hours’ notice of the industrial action.

The Australian Electoral Commission (AEC) will no longer be the default ballot agent for PABO and employers can choose an alternative agent who is approved by the FWC.

Where the AEC is the appointed PABO agent, the AEC will be able to seek orders for contravention of civil penalty provisions that relate to the ballot.

Mandatory conciliation may present an opportunity to resolve the dispute but will also take resources away from the business at a time when contingency planning may be occurring.

Respect@Work and the Fair Work Commission sexual harassment jurisdiction

The new Part 3-5A of the FW Act deals explicitly with sexual harassment. The key changes are the prohibition of sexual harassment and the new dispute resolution framework. The changes result in the FWC having a wider discretion to make orders against individuals as well as employers. The changes impose onerous obligations on employers, who must take all reasonable steps to prevent employees and agents from engaging in the unlawful acts. This means that employers will have to be proactive in implementing processes, procedures and other measures that are targeted at preventing sexual harassment in the workplace.

Sexual harassment and discrimination

Prohibition on sexual harassment

The FW Act prohibits sexual harassment in connection with work, reflecting the definitions in the model WHS laws. This applies to workers, prospective workers and a person conducting a business or undertaking.

Principals can be held vicariously liable for acts of their employees or agents unless they can prove that they took all reasonable steps to prevent the unlawful acts. Individuals and body corporates may have accessorial liability if they are ‘involved’, including for compensation and penalty orders.

Sexual harassment claims

Workers may apply to the FWC seeking stop sexual harassment orders for future sexual harassment and to apply for compensation for past sexual harassment.

Stop sexual harassment order

On application, if the FWC is satisfied that a person has been sexually harassed and that there is a risk they will continue to be sexually harassed, it can make any order it considers appropriate (other than an order requiring payment of a pecuniary amount) to prevent the aggrieved person from being sexually harassed again.

In considering the terms of a stop sexual harassment order, the FWC must take into account:

- the outcomes of any final or interim investigations into the alleged conduct being undertaken by a third party

- whether there are other procedures available to the aggrieved person and if so the outcome of those procedures; and

- any matters the FWC considers relevant.

The FWC has a wide discretion as to the types of orders it can make (although it cannot order the payment of money). Orders can be made against the individuals involved as well as the employer and the types of orders made will mirror those under the anti-bullying jurisdiction.

Dealing with sexual harassment disputes in other ways

The sexual harassment prohibition is also supported by a new dispute resolution framework, modelled on the compliance framework in the FW Act that applies to general protections dismissal disputes. The FWC may deal with disputes about sexual harassment which relate to past harm caused by sexual harassment. This framework is similar to that which applies to the general protections dismissal dispute provisions. A time limit of 24 months after the last alleged contravention applies.

If an application for compensation is made to the FWC to deal with a dispute that does not consist solely of an application for a stop sexual harassment order, the FWC may deal with the dispute other than by arbitration. This may include mediation or conciliation, or by making a recommendation or expressing an opinion.

If the dispute remained unresolved and the FWC is satisfied that all reasonable attempts to resolve the dispute have been or are likely to be unsuccessful, the parties could proceed to consent arbitration in the FWC or, in the absence of consent, applicants may make an application to a Court. An application to a Court will generally need to be made within 60 days of a certificate being issued by the FWC.

Jurisdiction

A Court can order a party that has contravened the sexual harassment prohibition to pay a pecuniary penalty as well as making other orders (e.g. compensation). The imposition of a pecuniary penalty is significant, as under existing anti-discrimination legislation the primary remedy available is damages. Employers may now be exposed to pecuniary penalties separate to substantiated injuries or damage. The maximum penalty a Court can order for each contravention will be 60 penalty units ($16,500 for individuals and $82,500 for corporations from 1 January 2023). This is consistent with the maximum penalty that currently applies under the FW Act in relation to analogous conduct, for example, discriminatory adverse action.

Anti-double dipping provisions are inserted to prevent a person from obtaining multiple remedies in relation to the same conduct. This prevents the concurrent operation of State and Territory anti-discrimination laws and, except in some limited circumstances, work health and safety laws (to the extent they deal with sexual harassment).

Anti-discrimination and special measures

There are three further protected attributes being introduced under the FW Act in the anti-discrimination provisions: breastfeeding, gender identity and intersex status. These changes align the FW Act with other Commonwealth anti-discrimination legislation.

‘Special measures to achieve equality’ will be confirmed as being matters pertaining to the employment relationship and are not discriminatory terms and therefore able to be included in an enterprise agreement.

Changes to individual employment arrangements, gender equality, equal remuneration, and flexible working

A key focus of the changes to the FW Act has been the enhancement of job security and gender equality. A raft of changes generally relating to individual employment arrangements have been introduced. This includes new powers being provided to the FWC to deal with disputes, consultation-type obligations for employers in certain circumstances, and prohibitions on particular contractual terms.

New limits on the use of fixed-term contracts beyond a period of two years or for more than one renewal are intended to ensure that workers on fixed-term contracts have access to secure and permanent employment. The changes also ensure that fixed-term contracts are only used where appropriate and employees are otherwise afforded due process where their employment is terminated. Further, an increase to the small claims threshold will provide a simpler pathway for employees to attempt to recover underpayments.

The changes to unpaid parental leave, flexible working arrangements and the introduction of expert panels and pay secrecy prohibitions have been made with a view to, among other things, promote and achieve gender equality in the workplace. In addition, gender equality is now enshrined as an object of the FW Act, meaning the FWC must have regard to matters of gender equality when exercising any of its powers and performing its functions.

Individual employment arrangements

Job security

Job security has been introduced as an object of the FW Act, which means the FWC must take job security into account when performing its functions or exercising powers, including dispute resolution, setting minimum wages, setting Modern Award terms and conditions, and approving enterprise agreements.

Prohibition on fixed-term contracts

The changes prohibit the use of fixed-term contracts where the term extends beyond two years or where the contract provides that it may be renewed more than once. Any contract term that has the effect of making a fixed-term contract last for more than two years, or be renewed more than once will be void and severed from the contract. These restrictions apply where the work being done under the contract or the renewable contract is the same, or substantially the same. There are also provisions about consecutive contracts where you have two contracts which together run for more than two years.

There are some exemptions where fixed-term contracts will continue to be allowed, including, for example:

- the employee is performing a distinct and identifiable task involving specialised skills

- the employee is engaged on a training arrangement, such as a traineeship or apprenticeship

- the employee is engaged to perform essential work during a peak demand period

- the contract is to undertake work during emergency circumstances

- the contract covers another employee’s temporary absence

- the employee earns over the high-income threshold

- the employee is performing government funded work, or work subject to other funding, where the funding is payable for more than two years and is unlikely to be renewed after that time

- the contract relates to a governance position in a corporation or association with a time limit under the relevant governing rules; and

- a Modern Award covers the employee and includes terms that permit a longer period.

There are anti-avoidance provisions; for example, dismissing for a period and re-engaging, delaying re-engaging, changing duties, or hiring a different employee to perform the same work.

The Fair Work Ombudsman will also prepare a fixed-term employee information statement that must be provided to fixed-term employees.

The FWC will be empowered to deal with disputes relating to fixed-term contracts, including by consent arbitration. Employees may also use the small claims process for a declaration of contract obligations or to get entitlements to redundancy pay or notice on termination.

This is a civil remedy provision which means penalties may be imposed.

Prohibition on incorrect pay rates in job advertisements

Jobs cannot be advertised at a lower rate than required by the FW Act, a Modern Award or enterprise agreement. Casual roles must include reference to the casual loading and piecework roles must specify the applicable piecework rate or that periodic rates apply. If the applicable pay rates change during the advertising period, the advertisement must be updated to reflect the new pay rates.

This is a civil remedy provision which means penalties may be imposed.

Enhancing the small claims process

The threshold for a small claims application to recover unpaid entitlements in the Court has been increased from $20,000 to $100,000 (exclusive of interest). Successful claimants will also be able to recover filing fees as costs.

Gender equality, equal remuneration and flexible working

Gender equality

Gender equality has been introduced as an object of the FW Act, which means the FWC must take gender equality into account when performing its functions or exercising powers, including dispute resolution, setting minimum wages, setting Modern Award terms and conditions, and approving enterprise agreements.

Expert panels

New expert panels have been introduced within the FWC that aim to tackle low pay and conditions in the female dominated care and community sector and to help attract and retain workers. These panels will provide the FWC with additional expertise in these sectors to enable them to better assess pay and working conditions. The introduction of the Pay Equity Expert Panel, Care and Community Sector Expert Panel and Pay Equity in the Care and Community Sector Expert Panel will make it easier for the FWC to order pay increases for workers in industries that are low-paid and female dominated.

Pay secrecy

A new workplace right has been added to the FW Act that allows employees to ask other employees about, and disclose their own, remuneration and relevant conditions of employment, such as hours of work. This allows employees to use this information to determine whether their remuneration is fair and comparable to others in the same workplace and/or industry. Employees cannot be compelled to disclose information about their remuneration and retain the right not to share this information if they do not want to.

As the right to disclose and ask about pay and conditions is a workplace right, an employer will breach the general protections provisions of the FW Act if they take adverse action against employees for doing so.

Existing pay secrecy clauses in employment contracts or other industrial instruments are now of no effect, meaning they are effectively severed from the contracts. Employers are prohibited from entering into any new contracts that contain pay secrecy clauses, with civil penalties applicable where this prohibition is not complied with.

This does not extend to contractor/consulting arrangements nor to release agreements.

Flexible working arrangements

Family and domestic violence and pregnancy have been added to the existing flexible working arrangements provisions allowing employees to make requests in these circumstances.

The employer is required to discuss the request with the employee and genuinely try to reach an agreement before refusing a request.

Only after taking these steps can an employer refuse a request, on account of reasonable business grounds (which are unchanged), which must be done having regard to the consequences of the refusal for the employee.

To refuse a request for flexible working arrangements, an employer must:

- discuss the request and genuinely try to reach agreement with the employee about other changes that can be made to accommodate their circumstances

- consider the consequences of the refusal for the employee

- refuse only on reasonable business grounds; and

- provide the refusal in writing, including the details of the reasons for refusal and any other changes the employer would be willing to make that could accommodate the employee’s circumstances.

The employer will also need to further explain and particularise its reason for refusing a request and include the extent of changes that the employer could support (if any). The refusal must also outline the new dispute and arbitration options.

The FWC will be empowered to deal with disputes about flexible working arrangements, including by arbitration where an order could be made to affirm the refusal, grant the employee’s request or make other changes to accommodate the employee.

For those dealing with Modern Award based flexible working requests, this is more of the same.

Unpaid parental leave

Additional requirements have been added for an employer to refuse a request to extend unpaid parental leave.

When an employee makes a request to extend a period of unpaid parental leave, employers must discuss the request with them, and if they refuse the request, must provide the reasons for refusal in writing. If there is a different extension period that the employer can agree to or is willing to consider, the employee should be informed of this in the written notice.

The FWC will be empowered to deal with disputes about refusing to extend unpaid parental leave, including by conciliation, mediation or arbitration.

Introduction

Changes to Enterprise Bargaining

Changes to industrial action (strikes, lockouts and bargaining disputes)

Respect@Work and the new Fair Work Commission sexual harassment jurisdiction

Changes to individual employment arrangements, gender equality, equal remuneration, and flexible working

Podcasts Series: Understanding the Impact of Changes to Workplace Laws

Additional Resources

Podcasts

Understanding the Impact of Changes to Workplace Laws

S04E01 The new world of workplace bargaining

14 December 2022

14.00

-

The new world of workplace bargaining (single employer and industry)

Dec 14, 2022 • 00:15:00

Steven Amendola and Brendan Milne discuss the new world of enterprise bargaining under the Government’s new legislation.

Additional Resources

December 2022

Webinar

What you need to know about important changes to workplace law from December 2022

October 2022

Insights

Secure jobs, better pay – Australia’s workplace relations overhaul